Who Are the Superstars in the Human Microbiome?

October 20, 2022

A parallel observation occurring as humans age and develop the common age related diseases is that the intestinal microbiome shifts to a different population. That begs the question whether these are simply unrelated changes or does one contribute to the other. In the previous blog I discussed the interesting study which found that fecal medical transplant (FMT) from young, healthy mice could improve inflammation, diabetes and obesity in older mice. This suggests that the change in microbiome composition may in fact contribute to the development to those diseases common to aging.

The next question was if FMT from healthy to diseased humans would have the same impact as it does in mice. The answer is yes. Unfortunately the only current FDA approved use of FMT is to resolve a difficult to treat intestinal infection, C. difficile. Research on using this procedure for other health problems such as systemic inflammatory disease and diabetes is underway.

The third question to arise is, given the expense and difficulty of FMT, which is done with colonoscopy or endoscopy, could a disease improving microbiome be restored with oral probiotic supplementation. The answer is appearing to be yes but with the qualification that only if it is with certain targeted bacterial strains. Looking at comprehensive microbe screening of young, healthy and older and ill individuals has led to an understanding about what would be the ideal microbiome pattern to restore.

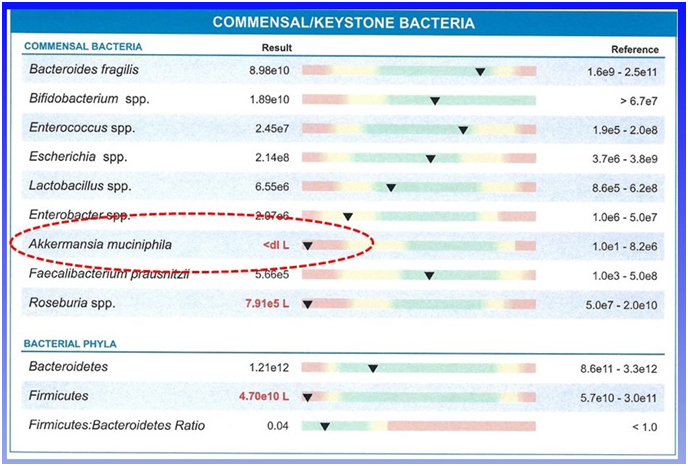

While the microbiome is very diverse, a few species called “keystone” species appear to be the key to a healthy microbiome. The most important appears to be Akkermansia muciniphila. Looking at what species declined in older and sicker individuals, this species was the most noticeable contrast with the younger healthier population.

Some of the disorders that this reduction in Akkermansia has been shown to correlate with include chronic liver disease, atherosclerosis, autoimmune diabetes, ulcerative colitis, type two diabetes, and obesity. The link to all of these disorders seems to be systemic inflammation which is a driving mechanism of these and many more health problems.

The other keystone species is Clostridia butyricum. Both of these species are now available in supplements and are often used with species of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium greatly increasing their effectiveness over most commonly used probiotics. That changing a few species in the gut could have such a profound impact on our health is surprising.

A separate question naturally comes up as to why does this disease-causing shift in our microbiome happen with age. It largely appears to be the result of the accumulation of challenges that occur during life with many of them related to modifiable lifestyle changes. We will discuss that prevention perspective in the next blog.