Can the Microbiome Changes with Age and Disease Be Corrected With Probiotics?

November 1, 2022

In the previous blogs we discussed the interesting work on altering the microbiome with fecal medical transplant (FMT) to correct inflammation, inflammatory related disease, diabetes, and other chronic health problems. The results are pretty dramatic. The problem is that FMT requires endoscopy/colonoscopy, cost and further FDA approval. Right now it is only approved to treat unresponsive gut C. difficile infection.

That question is resulting in a significant push to find out what specific bacterial species create these beneficial effects and can they help in supplemental form versus FMT. The first question was what specific bacterial species generate the positive effects. Comprehensive analysis of the changes in the fecal microbiome in younger, healthier subjects compared to the diseased subjects’ microbiomes has narrowed down the benefit to a small group of species.

This small group of species have been called “keystone” species as their presence or absence orchestrates the protective or punitive effects with their high presence or relative absence. The leader of this small group of keystone species is Akkermansia muciniphila (Ak). The graphic shows the differences in the species in the obese mice with inflammation and diabetes compared to the lean healthy mice. The largest decrease is that of Ak. Human studies have found the same result.

The main job of Ak is to metabolize mucin to produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which are used in extensive signaling to the cells that line the gut barrier.

Another benefit Ak imparts is that its metabolism of mucin stimulates the cells responsible for producing mucin to increase secretions of it. This increased mucin gives a layer of protection to the single cell gut epithelium which separates the contents of the gut and the immune layer of tissue below it. Bacterial molecules in the gut lumen called LPS and different food peptides can trigger inflammation so it is important to keep them in the gut lumen and not allow access to the immune layer.

A second keystone species called Clostridia butyricum works closely with Ak to maintain the gut barrier preventing “leaky gut” which is a potent inducer of systemic inflammation. These two keystone species are supported by several Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species which round out the keys to a healthy microbiome.

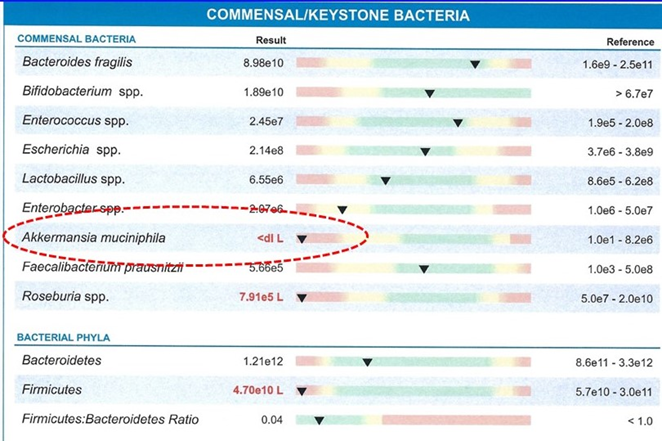

Newer microbiome testing allows the direct measurement of these keystone species enhancing our ability to isolate their possible role in an individual’s symptoms and disease. The example shows a test where Akkermansia muciniphila is <dl L which is below the detection level. This was in a subject with multiple inflammatory related health problems.

Up until recently, there has been a significant puzzle regarding our microbiome and our health. Why, when we can demonstrate that a shift in the microbiome is associated with many of the adult diseases has there been little success in attacking those with probiotics?

The solution appears to be that the focus has been on probiotic bacteria concentrating more on those species which make up the largest volume of bacteria rather than those which are the keystone species. Fortunately, now based on this information both Akkermansia muciniphila and Clostridia butyricum are available in supplements.

There is still one question on all of this with the microbiome. Why does the unhealthy shift in our microbiome happen across middle and upper ages? That we discuss in the next blog. As my mother-in-law who knew all of the Pennsylvania Dutch sayings would often say, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”