Stress Accumulates with Negative Health Effects

June 7, 2022

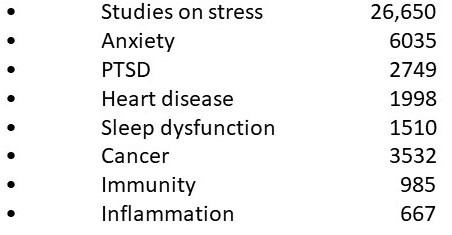

Perhaps the greatest overlooked aspect of disease risk is the impact of stress. A search of the topic “stress” in PubMed, the search engine for the National Library of Medicine reveals over 26,000 studies that have looked at stress and health. The majority of these studies examine a disease risk that is associated with stress. Over 2700 studies have looked at the relationship between stress and heart disease while over 3500 have looked at stress and cancer.

Understanding the changes in body function during stress helps to understand the disease relationships. In reality, we do not have a “stress response” but rather we have a “danger response”. This reaction to danger increased our chance of survival in a dangerous world. If we encountered a bear while searching for food, it was literally “fight or flight”. To prepare for this, heart rate and blood pressure increased significantly. Stress hormones like epinephrine and cortisol increase. Inflammation is upregulated to fight any infection if we would become wounded.

While these changes increased our chance of surviving the danger, they have negative health effects if they are sustained. Sustained increased blood pressure is hypertension. Sustained driving of heart rate can lead to palpitations, tachycardia and other heart rate abnormalities. Sustained stress hormone levels are associated with many health disorders. Chronic elevation of cortisol in the evening has been associated with greater volume loss in the hippocampus, the area of the brain that shrinks early in those with Alzheimer’s disease.(1)

While danger is typically brief, you “fight” and win or lose within a few minutes, or you take “flight” and will escape or be killed within minutes. If you win or escape, the stress response resets to normal within an hour, so no harm done. However, the memory of that experience is stored to heighten awareness of a danger that was encountered the first time.

In modern society, danger is typically not the problem, but rather chronic psychosocial stress is. A stressful job, financial stress, relationship stress, and many other mental stressors are common. The real concern is that psychosocial stress tends to be chronic and ongoing for many people.

Much of the body change that occurs in response to stress is driven by the changed activity pattern in the brain that drives “danger preparedness” in blood pressure, heart rate and hormone response. This stress receives prioritized memory as happens during danger.

Herein lies the problem with chronic stress. The brain learns through repetition, a process called neuroplasticity. The positive side of neuroplasticity is if we want to learn French, we study and repeat words over a long interval. The brain wires pathways to remember French.

Activating the stress response in the brain repeatedly over time wires the brain into a chronic response. Blood pressure response becomes sustained, hypertension and so on. Our normal default mode of body control resets from normal to an ongoing danger response. Danger signals are wired into an area of the lower brain called the amygdala which makes them a more indelible memory compared to non-dangerous events which are stored in other brain areas. While we may forget a lunch with friends several years ago, we do not forget the coiled snake we almost stepped on. This preferential handling of dangerous memory is also done with stress; we don’t forget it easily.

As would be suspected with this control being in the brain, direct brain conditions such as anxiety, depression and PTSD are common with sustained psychosocial stress. The brain resets its default state to “fight or flight” and the new pattern of body activation becomes disease causing.

One of the best gems I received at a conference on functional digestive disorders was to add two questions to the intake forms we use for patients with digestive symptoms such as abdominal pain and bloating. Those two questions are “do you have any trouble with anxiety or depression?” About 75% of those with functional digestive disorders such as IBS have associated anxiety or depression. All digestive activity is governed by the parasympathetic nervous or “rest, repair & digest” system. Continued activation of the sympathetic nervous system which controls “fight or flight” inhibits digestive secretions needed for digestion as well as digestive motility. Chronic stress rewires with the digestive tract into a non-functional pattern.

This concept of neuroplasticity or the ability to rewire the brain with repetition can be used in treatment. Techniques that are helpful to rewire the brain out of the stress activation pattern may include:

- Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation (tVNS)

- Heart rate variability biofeedback (HRV)

- Photobiomodulation (PBM)

tVNS – The vagus nerve is the main parasympathetic autonomic communication between the body and the brain. When activated the vagus nerve activates the brain centers involved in “rest and repair”. Over time this repeated stimulation exploits neuroplasticity re-establishing rest and repair as the default program of brain operation instead of fight or flight.

HRV – The heart is constantly speeding up and slowing down, a phenomenon called heart rate variability. This shifting is the result of alternating activation of the sympathetic nervous system which increases heart rate and activation of the parasympathetic nervous system which slows heart rate. Inhalation increases sympathetic activity and thus heart rate. Exhalation increases parasympathetic activity slowing heart rate. The observation of HRV during controlled breathing teaches to rebalance the activity in these two systems and with repetition, the brain gradually rewires.

PBM – The PBM is using light (photo) on living tissue (Bio) to change its activity (modulation). Visible light will not penetrate into the brain. The longest wavelength visible light is red which is 650 nM. Brain PBM is done with infrared diodes that have a wavelength of 1064 nM which will penetrate 40 mm. The infrared light activates cell ATP or energy production. The light is pulsing at a specific frequency inducing “entrainment”.

A good example of entrainment is listening to a band. Everyone listening is doing something to the beat of the music such as taping their feet, hands or some other movement in the same frequency of the beat. The brain will follow light frequency the same as sounds producing brain EEG waves in a similar frequency. For example, a 10 hertz pulsing light will increase brain alpha waves which are 10 hertz. This moves the brain to the same relaxed frequency and state as does meditation which is helpful for anxiety and PTSD.

For cognitive problems, the higher frequency brain waves called beta and high beta become weak. As these waves are between 13 and 40 hertz frequency they can be raised by entrainment with those frequencies. Sleep involves transitioning to lower frequencies called theta and delta which are 2-7 hertz so they are suited to helping sleep dysfunction.

Stress is similar to diet in that it has pervasive effects on our health. We have spent 3-4 decades trying to manage the health effects related to stress with medications. This is often unsuccessful and not uncommonly is associated with adverse effects. We have entered the age of treatment with techniques to treat the adverse effects of stress. They are effective and without adverse effects. For many, stress will not go away. Fortunately we can help the negative effects of stress go away.

- Knoops at el. BASAL HYOPTHALAMIC PITUITARY ADRENAL AXIS ACTIVITY AND HIPPOCAMPAL VOLUMES: THE SMART-MEDEA STUDY. Biol Psychiatry, 2010 Jun 15;67(12):1191-8.