Antibiotics and Our Microbiome

September 21, 2022

The human microbiome, or the microbes that live in and on us are vast and diverse. These microbes number 100 trillion with the majority residing in the digestive tract. For a perspective on 100 trillion, the number of microbes in the human microbiome is 10 times greater than the number of our own cells.

As we learn more about this microbiome, it appears to play a large roll in our health but also in our illnesses. The difference in the two outcomes relates to both the diversity in the number of species in this population and also the volume of the different species. A richly diverse microbiome helps us in several ways:

- It helps to control inflammation

- It helps balance digestive motility

- It is needed to produce the healthy metabolites from the phytonutrients in our food

- It helps to suppress the growth of opportunistic organisms and pathogens

Inflammatory control

Inflammation is an important driver of almost all chronic health disorders from arthritis to cardiovascular disease to autoimmune disease. While it is an important mechanism by which we fight acute infections and initiate repair of injured tissue, it becomes disease causing if it is sustained and pronounced.

The healthy gut bacteria ferment high quality fiber in our diet to produce short chain fatty acids which are important to our function. One of them, butyrate, has important anti-inflammatory properties.

Digestive motility

Most disorders of the digestive tract such as IBS have disordered motility either in the form of too much causing diarrhea or too little causing constipation. Many of the disruptions of motility are caused by an imbalanced microbiome.

Healthy metabolite production

The broad health properties in both food and herbs are thought to come from the phytonutrients such as flavonoids and polyphenols. These health benefits however, do not come solely directly from these in food/herbs but rather from metabolites of these phytonutrients generated by the gut bacteria.

Suppress the growth of opportunistic or pathologic organisms

The healthy microbes in the gut act somewhat like police officers on the street. If there are enough of them around, the bad actors tend not to show up. If the microbiome is unhealthy, there is an increased risk of adverse gut infection. Perhaps the most known is hospital acquired Clostridium difficile infection. It is most commonly caused by disruption of the microbiome by antibiotic use.

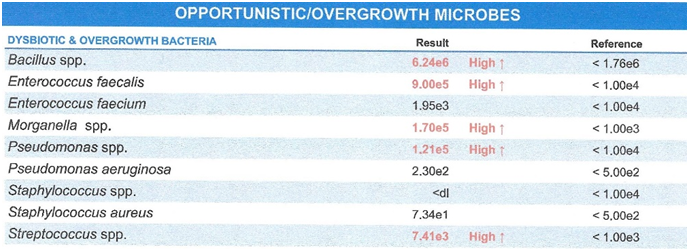

A more common problem is dysbiosis which is an overgrowth of organisms which are not severe disease causing pathogens but microbes that disturb function often causing symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, reflux. They disturb motility and typically cause inflammation often generating systemic symptoms such as joint pain, skin disorders like eczema and brain fog.

Antibiotics

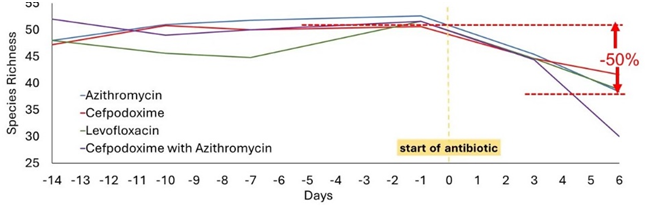

It has been known for some time that antibiotics disrupt the normal microbiome. Some new study has put an exclamation point on the degree to which this occurs.(1) The study looked at the changes in the microbiome following just 6 days of the use of 1 of 4 different antibiotics. The study found that the richness or diversity of the normal bacteria was significantly reduced.

Follow-up stool samples at 2 months found that the diversity of the microbiome came back in most subjects, but the bacteria present were not the same as they were originally. This is a finding that normally occurs with aging where the composition of our microbiome changes being made up of fewer helpful bacteria and more not so helpful ones. Antibiotics seem to accelerate this age-related shift.

In 15% of the subjects even the diversity of the microbiome failed to return to normal after 6 months. This shift was similar to the microbiome that has been found in ICU patients who are those especially susceptible to Clostridium difficile infection. All of this suggests that our microbiome is altered unfavorably in all persons taking antibiotics and especially unfavorably in about 1 in 6 who do so.

One of the researchers in this study, Winston Anthony, at Washington University School of Medicine summarized, “This means antibiotics are fundamentally restructuring the microbiome”. W. Joost Wiersinga, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Amsterdam who has separately studied the effects of antibiotics in healthy people, commented on the agreement of this new study with their findings, “it adds to the evidence that antibiotics can have major detrimental effects on the gut microbiome in healthy adults.” Their study went out 31 months and found that these changes to the microbiome were still present.

We have become too loose in the use of antibiotics in many cases. They can be life saving in some circumstances but are not a panacea to be used without thought. We have under-appreciated the role of our microbiome in our health. It is one of the factors that deserves careful analysis after antibiotic use.

The microbiome can often be restored to a healthier state by a combination of broad spectrum probiotics to restore the healthy bacteria, herbal antimicrobials that reduce the dysbiosis bacteria, nutritional support to restore the gut lining and prebiotic (fermentable fiber) to feed the healthy bacteria.

Anthony et al. Acute and persistent effects of commonly used antibiotics on the gut microbiome and resistome in healthy adults. Cell Reports, 2022;39:110649.

Haak et al. Long-term impact of oral vancomycin, ciprofloxacin and metronidazole on the gut microbiota in healthy humans. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2019;74:782–786.