When Gluten Causes Immune Attacks Against Our Own Tissues

January 27, 2022

The most commonly known autoimmune disease associated with gluten consumption is celiac disease. The disease involves an immune reaction against a small segment of a peptide in gluten called an epitope. Once the immune system recognizes this epitope and mistakes it for a dangerous invader such as a virus, it can activate an attack against it. At this point most will develop symptoms of IBS such as abdominal pain, bloating and some degree of constipation and/or diarrhea but not celiac disease.

If this exposure continues the immune system may increase the degree with which it attacks including activating B cells or those which make antibodies. This is where the risk of autoimmunity or attack against “self-tissue” increases. Our own tissues may contain a similar segment of peptide or epitope which can be mistaken by the immune system as the gluten epitope producing antibodies that now attack that tissue. There is such an epitope in an enzyme in the small intestinal lining tissue called tissue transglutaminase (tTG). These antibodies then destroy the small intestinal lining which is the classic finding on endoscopy biopsy for the diagnosis of the disease.

Perhaps less well appreciated, this type of gluten triggered attack can occur in other areas of the body causing other autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis which is the most common cause of hypothyroidism. While this disease affects about 2% of the population without celiac disease, antibodies against the thyroid gland are found in 15-24% of those with celiac disease, a 7 to 12 fold increase. Similar high rates of autoimmunity to other areas associated with celiac disease have also been found for type 1 diabetes, pernicious anemia, autoimmune liver disease, and several others.(1)

Most individuals who have an immune sensitivity to gluten will not develop celiac disease and will have what is referred to as non-celiac gluten sensitivity or NCGS. It is estimated that the rate of NCGS is 8-10 times higher than celiac disease. The big question then becomes do individuals with NCGS have higher rates of autoimmune diseases similar to those who have celiac disease? The answer is yes.

A study of 131 subjects with NCGS found that 29% also had at least one active autoimmune disease compared to only 4% of control subjects. As with autoimmunity associated with celiac disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis/hypothyroidism was the most common autoimmune disease associated with NCGS. Anti-nuclear antibodies or ANA antibodies are the most common antibody against self-tissue in NCGS being present in 46% compared to 2% of control subjects. ANA is often the first antibody against self-tissue in several autoimmune diseases such as lupus. It will often show up several years before diagnosable lupus develops.

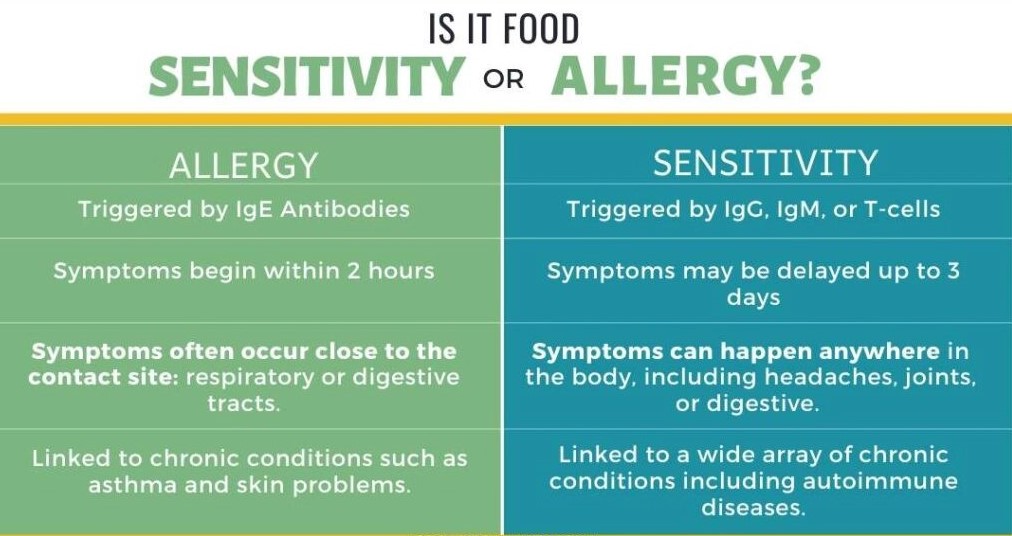

Antibodies against self-tissue will often reduce or return to normal if the original immune trigger can be found and is strictly eliminated as in the case of gluten. Although gluten is the most common trigger of food sensitivity and immune reactivity against self-tissue, it is not the only one. Beta casein in dairy is a close second but other food components may be the culprit. Food sensitivity testing is particularly important in those with autoimmune disease. Ideally, the identification of a food sensitivity may prevent the development of autoimmunity and should be a consideration in anyone with any digestive symptoms which are the typical first manifestations or the common peripheral symptoms such as skin conditions, joint inflammations or brain/mood disorders.

- Shaoul R, Lerner A. Associated autoantibodies in celiac disease. Autoimmunity Reviews 6 (2007) 559–565.

- Losurdo et al. Extra-intestinal manifestations of non-celiac gluten sensitivity: An expanding paradigm. World J Gastroenterol, 2018;24(14):1521–1530.