Stuff Disguised as Food – How to Read a Label

March 30, 2011

Perhaps the best rule of good nutrition is to eat as much food as is possible that does not need a label (simple, whole foods). Unfortunately, this is not always possible and we must enter the jungle of packaged foods. The best defense in doing so is knowledge of how to understand from the label what it is really made of.

Label Reading Rules

Rule #1 – Read the grams of sugar/serving

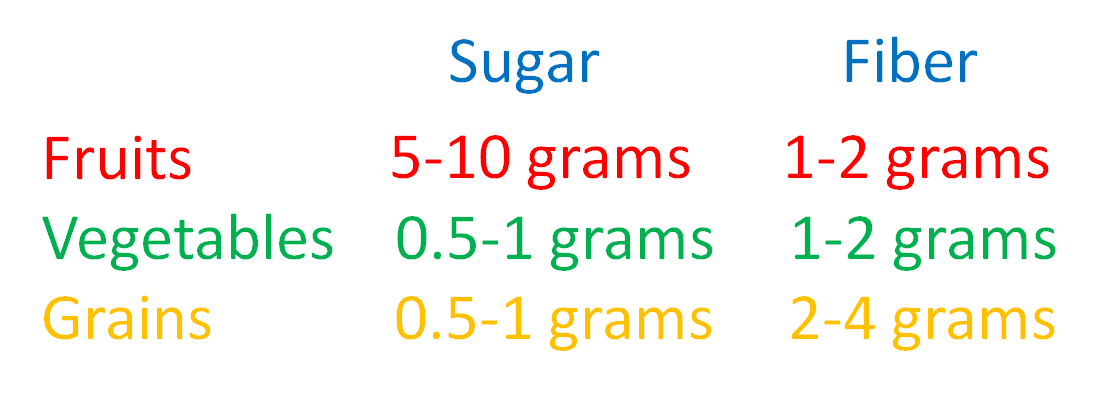

By law the grams of sugar/serving must be listed in the Nutrition Facts box. The real question is how much should that be? All carbohydrates contain sugars inherently. However, most that are in “man altered foods” have added sugar. Generally, the three dominant families of whole carbohydrates should have the following sugar amounts per serving:

These foods in their whole form will also have a significant amount of fiber. The combination of the fiber with the natural sugars is what causes the sugar in whole carbohydrates to be absorbed slowly. This allows the body time to burn them for energy rather than converting them to fat and storing them.

Basically, the greater the sugar content versus the fiber content, the greater the metabolic stress a food creates and the greater the fat production.

Rule #2 – Find out what chemicals are in it

Chemicals serve no nutritive purpose and they are put in foods only to change appearance, texture or to preserve the item. All chemicals are “zenobiotics” which means you cannot break them down and turn them into energy. They must be eliminated through enzyme pathways in the liver that are typically over-worked by our chemical society.

Chemicals serve no nutritive purpose and they are put in foods only to change appearance, texture or to preserve the item. All chemicals are “zenobiotics” which means you cannot break them down and turn them into energy. They must be eliminated through enzyme pathways in the liver that are typically over-worked by our chemical society.

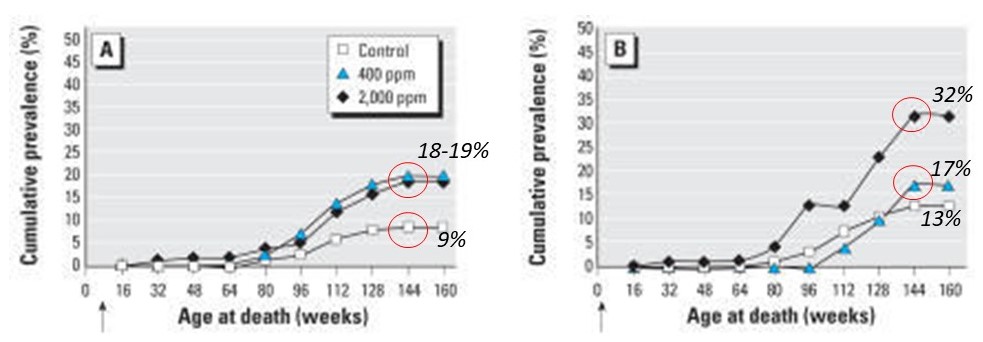

When the liver is overworked and these zenobiotics are not cleared quickly enough, they create problems. An example of this is the artificial sweetener aspartame. It is temporarily broken down into formaldehyde until the liver can finish its breakdown. Formaldehyde is well known to be associated with the risk of lymphoma. Animal studies have now shown that chronic aspartame exposure which mimics ongoing human use levels is associated with a doubling of the risk of different cancers. The figure below from one study shows that rats exposed to aspartame during post-natal life ( figure A) and both during the prenatal period and throughout life (figure B) have twice the risk of a cancer death with older age. (White dots are no exposure while the blue and black are different levels of exposure)

Life-Span Exposure to Low Doses of Aspartame Beginning during Prenatal Life Increases Cancer Effects in Rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2007 September;115(9):1293-1297.

At 144 weeks of age the rats consuming aspartame post-natal had a cancer death rate of 18-19% compared to the non-consuming controls at 9%. For those exposed to it pre-natal and postnatal the difference is even more dramatic with rates of 17% and 32% for the higher and lower dosages compared to the cancer death rate of 13% for the non-consuming controls.

The data with aspartame is controversial as is always the case when there are conflicting business and scientific interests that influence the process of investigation.

A great video by Russell Blaylock, MD, discusses the aspartame controversy:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lqIFDoOwSFM&feature=related

Because of the above controversy, aspartame is slowly going away only to be replaced by the next chemical sweetener du jour. We don’t know what the problems are yet with this newest generation; rather we only know that they will be apparent in about a decade of use. We close the barn door after the horse is long gone.

It is difficult to investigate the influence of chemicals in disease origin as it is likely the different chemicals alone do not cause the greatest risk, rather they do so when they are combined with dozens of other chemicals. It is suggested that it is the total chemical load which overwhelms our detoxification systems and immune systems leading to problems.

The general philosophy of the amount of chemicals we should tolerate in our food is none. Even without food we receive multiple chemical exposures from just about every other facet of life.

To see what chemical exposure is in each food read the ingredient list. Read each ingredient and quickly judge each one as a food, chemical or NI (no idea). Add up the chemicals and NIs (most are chemicals) and judge how much of what you are eating is actually chemical. It is not unusual to find that 10-20% of food is actually not food!

Rule #3 – Look for trans fats

Trans fats are chemically altered unsaturated fats that are fairly commonly used in packaged food and in commercial food cooking. While they are made from fats that were potentially somewhat more healthy called polyunsaturated fat, they are the worst fat that could be consumed because of their altered form.

Trans fats are made by hydrogenating polyunsaturated fats. They are made by forcing hydrogen onto the molecule to make it solid at room temperature (a feature of saturated fat such as butter). The problem is that when this is done some of the hydrogen ends up on the wrong side of the molecule making the body unable to handle the fat. As you can guess from this description, a trans fat is a “hydrogenated” oil.

The data on their ill effects of disease risk such as heart disease wasn’t available until a decade or more after their use began. Unfortunately the food industry became addicted to them as they are cheap and stable. When the FDA finally dealt with trans fats labeling regulations, the food industry aggressively lobbied and influenced the labeling requirements.

The law allows up to one-half gram to be used per ingredient and rounded down to zero. However, if you know the rest of the story it all begins to look like a big sleight-of-hand trick:

• The consumer typically knows to look for a trans fat but has to know they can be called a hydrogenated fat in the ingredient list.

• Multiple hydrogenated oils can be used at a half gram each increasing the content above the limit but can still be reported as “zero”. 1/2 gram (rounded to “0”) + 1/2 gram (rounded to “0”) + 1/2 gram (rounded to “0”) mathematically is 1.5 grams but in “labelese” is just “0.”

• The reported grams are “per serving”, and the serving size can be set at artificially low levels by the manufacturer. A tiny bag of chips may have the 1.5 grams or zero reported grams, but the bag is 2 servings. The real trans fat exposure is 3 grams per bag, or what the average person would eat.

• The heart healthy designation only applies to the grams of saturated fat. While the negative impact of saturated fat cannot be shown until exposure is 25 grams/day or more, it can be seen with trans fat at 6-7 grams/day exposure. This level can be reached with just 2 foods with the “zero grams per serving”.

As consumer knowledge of the dangers of trans fats and the deceptive labeling practices increases, the food industry is responding using the next great man-made synthetic fat. These are called inter-esterified fats or esters of fatty acids. The early research on them shows that they are actually more harmful than trans fats/hydrogenated oils.

As consumer knowledge of the dangers of trans fats and the deceptive labeling practices increases, the food industry is responding using the next great man-made synthetic fat. These are called inter-esterified fats or esters of fatty acids. The early research on them shows that they are actually more harmful than trans fats/hydrogenated oils.

Unfortunately, there will be a 10-year or more “grace period” of their use before their effects are commonly well understood forcing the system to take some action against their use or requiring better disclosure.

Rule #4 – Look for “altered foods”

This may be the most tricky group to pick up on because part of the ingredient name is actually a food. An example is hydrolyzed vegetable protein. This is vegetable source protein “predigested” with hydrochloric acid to release glutamate. Glutamate imparts a strong taste to food that typically drives greater consumption. The most notorious form of glutamate is monosodium glutamate, or MSG. Its ill effects are well established.

Another video by Russell Blaylock, MD discusses the impact of MSG in food:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKSwpifzUDw

If MSG or a similar glutamate is directly added to a food by the manufacturer who sells directly to the consumer, it has to be listed on the label. It can be made as another ingredient by a wholesale manufacturer and then added as that ingredient by the second manufacturer who sells to the consumer and only the term “hydrolyzed vegetable protein” need be used on the label.

The list of “altered foods” that have food words in the title are many. A key in recognition is the use of a term that suggests something has been done to it or a vague description of what its origin is. Modified food starch is a good example. Why is it modified, and what is the food it is from? If it is just the real food, it will simply have the real food name. Dr. Blaylock has a great book out, “The Excitotoxins: The Taste that Kills”. In it he has an extensive list of altered food products, and those truly interested will find this book helpful.

Rule #5 – The quality of a packaged food is inversely related to the number of ingredients. If it has more than 6-8 ingredients, don’t eat it.

Rule # 5 I heard in a great presentation by a cardiologist taking to primary care physicians about how to give patients food rules that work in the limited time they have with patients. It perhaps is my favorite as, in many ways, it will automatically take care of almost everything discussed above. As you look at labels to screen them through rules 1-4, try to find something with more than 12-15 ingredients that does not include more than one of the problems discussed above.

Summary

The first thing one would conclude from studying food labels is that the regulations make understanding food complex and confusing. In many ways, that is the goal or what we don’t know (understand) can’t hurt us. Nothing could be further from the truth.

If you look at labels considering the 5 rules above, a major piece of the packaged food problem will be fixed. The best strategy, however, may just be to not eat any packaged food. That way we know that no one has messed with it.